Title:

Big and Bold: the Audacity of Shared Metadata, a keynote speech for the CILIP Metadata and Discovery Group 2020 Conference

Summary:

It takes a lot of nerve to create an international norm. Our current systems and standards are showing their age, but when they were created they were groundbreaking. What can we learn from the people who constructed these standards? How can we devise our own revolutionary future? Let’s imagine new possibilities for the Metadata & Discovery Group together.

Video:

Text of talk:

Hello! My name is Violet Fox, I use she/her pronouns, and my Twitter handle is @violetbfox. Today, let’s talk about big and bold ideas.

For accessibility purposes and anyone who would like to follow along with text in front of you, you can find the full script of this talk by going to tinyurl.com/mdg2020.

I want to take a moment to thank you for allowing me to be a part of your day, I am so excited to be with you here, although I’m sorry we can’t be together physically. I want to thank the conference organizers for their hard work, as well as everyone who will be presenting and participating. I’m looking forward to learning from you at the rest of the conference this week. I do want to note that these are my personal opinions, not that of my employer.

With that, let’s get started.

First off: there’s no need to adjust your monitor’s settings. You are looking at twine. More specifically, you are looking at a twine ball. Even more specifically, you are looking at the world’s largest twine ball created by one man.

As I pull away, you’ll see that it’s challenging to get a good shot of the twine ball because of the glass enclosure, especially on such a beautiful sunny day, but hopefully you’ll get a sense for just how big the twine ball is: 12 feet high (about 3 and a half meters) and 40 feet around (that’s about 12 meters). It’s in this fancy gazebo, and there’s a museum and souvenir shop just behind it to the left.

The man who created this twine ball was Francis A. Johnson. He was a farmer, and he started wrapping twine when he was 45 years old. You’ll see on the sign that they point out that this is the largest twine ball in the world… that was created by one man. There are three other contenders to the “world’s largest twine ball” title: one is larger, one is heavier, but this one is the original, the one that started the trend. Weird Al Yankovic wrote a song about it, if you’re the kind of nerd who listens to 7-minute Weird Al songs about a roadtrip to see a twine ball.

I spend a good amount of my free time thinking about road trips to see roadside attractions, especially giant versions of smaller things. Here’s me with a very large turkey, here in Minnesota, and a very large strawberry in Iowa, and a very large cow in North Dakota. I even write a zine about the roadside attractions that I’ve seen and about their cultural significance.

The theme of this year’s conference was really intimidating: what did I have to say that was “big”? But then I realized I love big things! I may not have super genius things to say, but I can certainly talk about the joy of things that are big and bold.

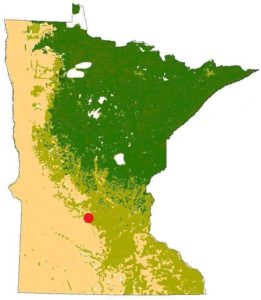

While I’m talking today, I’m going to show you video that I took in Darwin, Minnesota, population about 350 people. To help orient you, here’s a map of the continental United States with a red dot marking central Minnesota, and here’s a map of Minnesota with Darwin marked with a red dot. You can see Darwin is right on the edge of where the prairie meets the forest, it’s a unique landscape. Before colonization, this land was inhabited and maintained by the Dakota people, it was all prairie grassland. Now it’s primarily used for growing soybeans and corn.

So as you watch the corn grow and the wind blow, let me finally talk about libraries. First I’ll tell you what I do, then I’ll talk about some library history, and finally I’ll ask some questions about what kind of a profession we want to build together.

My job is that I’m one of the editors of the Dewey Decimal Classification. There are four of us on the editorial team, two full-time editors and two part-time volunteers. And the job that we do, we essentially make up the numbers in Dewey. Sometimes I’ll joke about having a big dartboard with numbers 1 through 10 and then we just pick whatever number comes up to add to the classification, but I’m kidding, the job involves a lot of research into publication trends and whatever subject we’re focusing on to make revisions, and it involves a lot of talking with library workers around the world to figure out what’s not working well in Dewey and how we can make things work better together. As you can imagine, the work to revise Dewey never ends, there’s always more topics to incorporate and changes in the way we think about organizing knowledge.

As you might also imagine, I spend a lot of time thinking about Melvil Dewey, and the origins of the structure that I work within. Melvil is an unpopular figure in librarianship these days, and with good reason: if you haven’t heard much about him, or even if you have, I’d encourage you to read Irrepressible Reformer, Wayne Wiegand’s biography of Melvil. He’s a complicated figure: he was unmistakably racist, anti-Semitic, and a serial sexual harasser of women. In addition to creating the Dewey Decimal Classification, he helped found the American Library Association, Library Journal, and other significant institutions that last through the present day. A good part of the reason librarianship is a primarily female profession is due to his efforts. You can see that we really can’t ignore his legacy, even if your library doesn’t use Dewey. I think a lot about Melvil and the libraries he was working within, and how his view of the world affects the classification even today, even after 144 years of ongoing revisions.

The thing I can’t get over is the audacity of creating one system to organize all published knowledge. From our vantage point, that looks like arrogance, because it certainly was. At the same time, it was groundbreaking. Melvil was driven by efficiency; he thought it was incredibly inefficient that each library had its own shelving organization. And it was!

The thing about Melvil is that he had big plans. He wanted to reform things in the shape he thought things ought to be. He tried a bunch of different things, some of which worked out, the library stuff, and some of which didn’t work out, like trying to popularize spelling reform and the metric system in the United States. One of his most successful efforts was creating a social club in New York State, where he built a strong community, but one based on classism and white supremacy and anti semitism.

Clearly, he was a jerk, and worse. He had such small ideas about what was acceptable. What you and I have is a bigger perspective of the world. So I want to ask you: What if we could use the big and bold energy that Melvil had to build communities that were truly inclusive?

Let me jump forward a bit to talk about another big innovation in libraries: MARC. Many of you know the history of MARC better than I do, so I won’t belabor it, but I will just take a moment to say how truly cutting-edge MARC was in the 1960s. How incredible was it to have used physical card catalogs for years or decades, and then to have that same information available electronically. MARC was developed by Henriette Avram but was made possible by a team of people working together at the Library of Congress. Those of you who have been around for awhile know that that transformation didn’t take place instantaneously, there were decades of retrospective conversion, and some information has still never made it off of the physical catalog cards into an electronic environment.

In dealing with MARC now, there’s a sensation of being trapped by what was previously so successful. We know that the development of MARC was based on physical cards; they still had to be concerned with printing the information onto the cards. We know that many of our cataloging standards were shaped by the limitations presented by physical catalog cards. And we know that the hundred of millions of records in MARC, that legacy data, is a real challenge to deal with. As a profession we’re still battling with breaking free from the limitations imposed by MARC.

MARC was the result of a well-funded government agency and very smart people and gumption. What you and I have is way better technology than they did. We have access to incredible ways to arrange and manipulate data. So I want to ask you: What if we could use the big and bold energy that built MARC and build something even better?

The last library history moment I want to touch on is RDA, which is history in that it’s been talked about in some form or another since 1997, but of course, it is history that’s being written right now. The principles behind RDA are exciting, without a doubt: moving beyond the limitations of the card catalog. Being able to describe all types of resources, without preference to physical books. Making data elements discrete to have a flexible framework to interact with database structures today and in years to come.

But RDA has been a long time in coming, and I’ll say from my perspective, at this moment, I think there’s a real crisis of faith in RDA in the profession. There have been issues with dismissive leadership, issues with high cost, issues with incredibly challenging conceptual models. I am really rooting for RDA to succeed, and I hope that the RDA team can step up at this crucial time and demonstrate the value of RDA to library workers.

I want to take just a moment to talk about leadership and what it means when there’s a lack of leadership.

I live about 40 miles from Darwin, Minnesota, about 65 kilometers. When I was originally planning what I would do during this keynote, I thought I might set up my camera on my car’s dashboard and show the drive down, it’s very pretty scenery past farms and small towns, especially this time of year. But I pretty quickly remembered that the U.S. is in an election year, and the drive down is littered with a not insignificant number of campaign signs for Trump, with flags, and yard signs and a bus painted with “Make America Great Again Again”. And I’ve got to say, that’s pretty shameful to me, and I didn’t want to subject you all to that.

This administration has been a nightmare, and I want to be clear that in some cases it’s been lethal. The unrestrained promotion of white supremacy has led to increased vitriol and increased violence, most often against Black Americans, immigrants, and trans people. The unapologetic acceptance of the uncontrolled spread of the coronavirus in the U.S. is just more evidence of a leadership that is morally bankrupt.

Speaking broadly about any organization, when there’s failure in leadership, whether via a power vacuum, or through ineptitude, or through malevolence, it is incredibly painful. But what it provides is clarity. What are our values? How are we living up to our values? How are we failing to live up to our values? What is most important to us?

In cataloging, we’ve generally embraced the virtue of efficiency above all other considerations, following in the footsteps of Melvil Dewey. Our systems are built around efficiency of action, favoring less information over more. Our collaboration is aimed primarily to not duplicate work.

So I want to ask you: What have we given up by prioritizing efficiency? What if we chose different values to prioritize?

Our cataloging standards are built with the goal of providing information to the library user. It is drilled into us: think of the user’s needs. When we create authority records, we do detective work to enable the user to find information. But we don’t necessarily think about the author, the creator of a work, and their rights.

So I want to ask you: What if we took into account the entire information environment of a work while we were cataloging it? Not just focused on the user, but taking into account the needs and rights of the people being described in that work, the people who created that work, the people who will be impacted by that work, and the words we choose to describe that work.

Many people in librarianship still cling to the idea of neutrality, thinking that we can be neutral in our controlled vocabularies, because we’re librarians and librarians are inherently good and value neutral. That’s a viewpoint that holds us back in making the profession better. I’d like to wholeheartedly recommend all of the work of Fobazi Ettarh, and especially her concept of vocational awe, which describes the set of values that librarians have about ourselves and our work as inherently noble and good, which allows us to disregard the way that libraries have upheld oppression and allows us to ignore perspectives and critiques that challenge our view of ourselves.

Within classification, I’ve been influenced by the work of Hope Olson, and her book The Power to Name, as well as Melissa Adler and Joe Tennis, whose article about acknowledging and naming the harm done in knowledge organization has resonated with me. I think that recognition is crucial—the words we use while working in metadata are incredibly powerful, and can be used to oppress. The most notorious recent example is, of course, the Library of Congress Subject Heading “Illegal aliens,” and it’s frustrating that that dehumanizing language is still in libraries around the world because of Congressional action. In the past year I’ve chaired a working group through ALA reporting on libraries who have changed that subject heading their catalog. Our report was just published in June and we’re working on a website compiling information about how libraries can take action by changing this heading in their own catalogs.

I also think there’s some newer catalogers who can struggle with making decisions because they’re very aware of the power of the words we use, and they don’t want to cause harm. Continuing the work of Adler and Tennis, I have talked in the past about thinking of our work in classification and description as practicing harm reduction. I would echo what many have said but April Hathcock said particularly well: you’re gonna screw up. When it comes to trying to be respectful about racial identities, gender identities, disabled identities, there’s no way you’ll ever know everything you need to know to not screw up. As April advised, you need to acknowledge that and move forward, and have the ability to be gracious about accepting the harm caused and learning from your mistakes. We need to be intentional about making space in our practice to hear from people that we’re describing. We need to be transparent about how we use people’s personal information, and we need to build mechanisms that provide ways for hearing feedback about our descriptions. Really, we need to embrace the iterative nature of metadata. When I talk about the audacity of shared metadata, I am awed by the fact that librarianship was able to build this massive network of bibliographic records, and trust in each other to improve and build off each others’ work.

So much of this comes down to having humility: knowing that we won’t have all the answers and being willing to listen. Being willing to step back and not be the expert and hearing from others, especially those who have been intentionally shut out from our cultures, especially Black, Asian and minority ethnic folks, especially disabled folks. We’ve all heard this, many times, but there’s value in repeating it over and over, because our whole lives we’ve learned and internalized narratives that value white supremacy and heteronormativity and patriarchy and cisgenderism and ableism and classism, so if we want to disrupt those kyriarchical ways of making sense of our lives, we have to repeat alternate ways of thinking over and over. I’ve been impacted deeply by reading and watching science fiction to envision new worlds, and I’m indebted to my friend Sofia Leung and her scholarship for her ability to tie radical reimaginings of the world to our work in librarianship. Activist and organizer Mariame Kaba has a wonderful phrase, “Hope is a discipline.” And the truth of that is breathtaking and worth sitting with for a moment.

Over the next week, we’ll be hearing from people doing great work in library metadata, who are shaping the profession. As we listen and learn, I want to ask you: What are your values, both personally and professionally? I’d like to encourage you to think about your role in how libraries are creating and maintaining information, and consider what values you want to embody in your work. I have been lucky enough to hear Nicole Cooke, Associate Professor at the University of South Carolina College of Information and Communications, speak multiple times, and she speaks about considering the legacy we want to leave after we’re gone. I want to repeat what I’ve learned from her: what sort of profession do we want to leave the people who will be working after us?

Changing the name of the group to the Metadata and Discovery Group is a fantastic opportunity to rethink our approach to our work. We can be just as bold as the people who have shaped librarianship in the past. We just have to think big. Just like… and I hope you know where I’m going with this: the twine ball, we have to tie our work together to create something that shakes us out of our complacency. We’ve got to make our work visible, promoting the value of our efforts, just like this great sign. And we have to support each other and build our community, just like the folks of Darwin, Minnesota.

Thanks so much for your time this morning, I appreciate you going along on this trip with me.

References and inspirations:

- A Brief Visual History of MARC Cataloging at the Library of Congress (2017) by Ben Schmidt

- Darwin, Minnesota (undated) by LakesnWood.com

- Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds (2017) by adrienne maree brown

- From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in the Archives (2016) by Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor

- How Do You Want to be Remembered? : ACRL Keynote (2017) by Nicole Cooke

- Irrepressible reformer : a biography of Melvil Dewey (1996) by Wayne Wiegand

- Knowledge Justice : Critical Librarianship & Pedagogy Symposium Keynote (2020) by Sofia Leung

- The Power to Name: Locating the Limits of Subject Representation in Libraries (2002) by Hope A. Olson

- Report of the SAC Working Group on Alternatives to LCSH “Illegal aliens” (2020)

- Toward a Taxonomy of Harm in Knowledge Organization Systems (2013) by Melissa Adler and Joseph T. Tennis

- Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves (2018) by Fobazi Ettarh

- You’re Gonna Screw Up (2016) by April Hathcock