Welcome to the Disorientation Guide to Librarianship! Find more information and formatted/printable versions of the zine at the main page: violetbfox.info/disorientation.

Table of contents

-

- Front Cover

- Editor’s Welcome

- Dedication

- I Was the Only Woman on the Tech Team

- World War II Reading Program in Sauk Center, Minnesota

- If Libraries Aren’t Worried About the Tiny Things, How Can They Work on the Big Things?

- Values and Agency in Library Organizations

- The Emotional Labour of Libraries: an Australian-Aboriginal Perspective

- 1971 Library of Congress Sit-In

- The Art Librarian

- Did You Know That Libraries Are Not Accessible? Did You?

- Library Systems Are Not Perfect: Describing Transgender Children and Young People Using LCSH

- Segregation in Library Associations

- I Worked for a Director At a Small Library

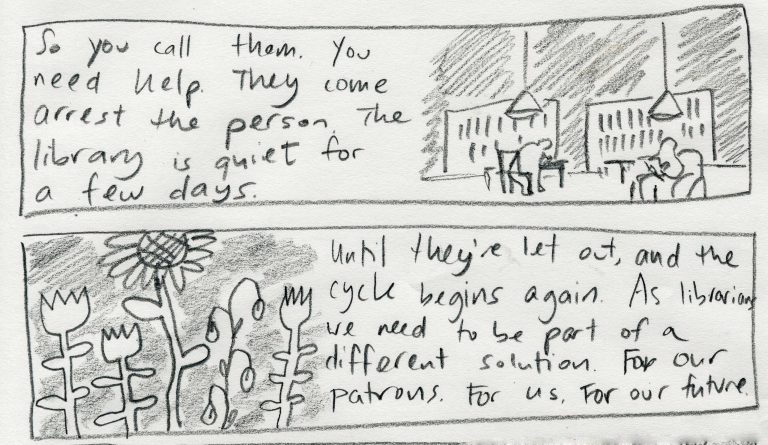

- Calling the Police

- Tips for New White Librarians from a First Nations Librarian from So Called “Australia”

- “Librarians Are Superheroes!”

- Librarians Are Revolutionaries?

- My Last Day at the Public Library

- Melvil Dewey: Father of Modern Librarianship & Racist Creep

- Rock the Boat with Your Privilege

- My Journey as an Assistant Professor

- Assumptions Are What We Do Not Realize We Are Making

- Why I Quit My Job

- Accommodations Provided on Request

- Should Children’s Librarians Care About Defunding the Police?

- Mildred Rutherford, Historian General of the United Daughters of the Confederacy

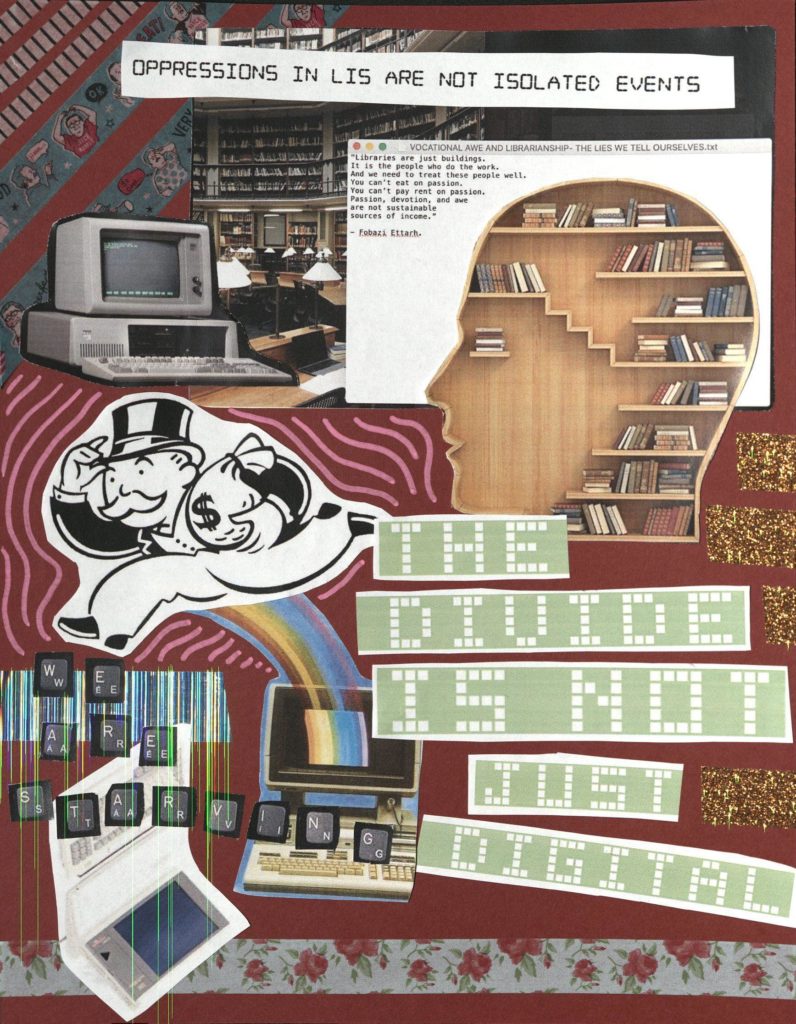

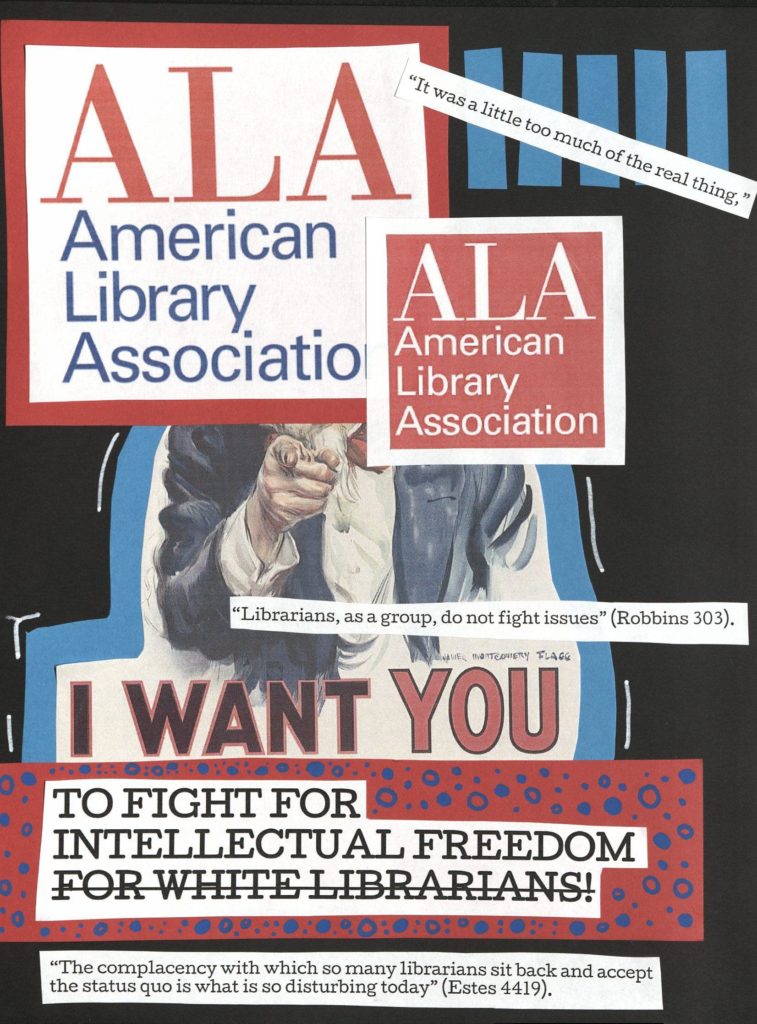

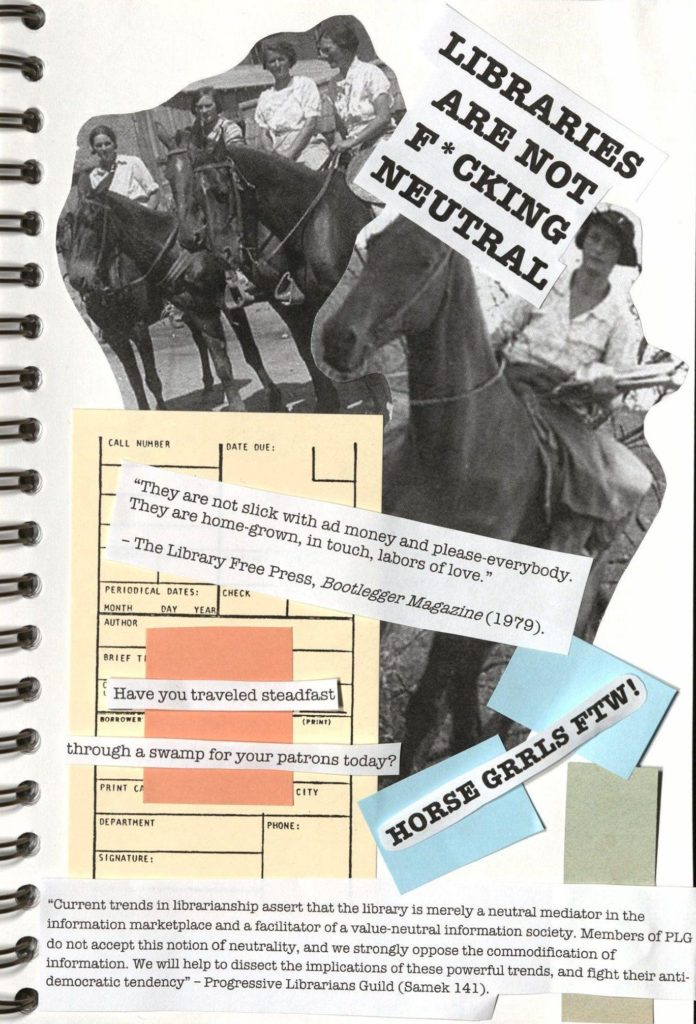

- Cover Collages

Front Cover

embroidery art by Jacqueline Morris

@jacquelinetextiles

Editor’s Welcome

In the longstanding practice of zinesters everywhere, I start this zine with an apology for being late. I stopped accepting submissions for the Disorientation Guide to Librarianship in September 2020 and I’m writing this intro in September 2021. The combination of being laid off, struggling to find a job in a recession, and depression was a brutal combo. To be honest, I figured I’d get back to compiling the zine “once COVID was over,” and, uh… not so much.

I am very excited to share this zine with you, tapping into the tradition of disorientation guides in higher education. The intention behind this zine is to be an accessible resource for people who are unfamiliar with structural oppression and injustice in librarianship. The Disorientation is intended to be a critique of library values and a guide for people fighting injustice in librarianship. The target audience is LIS students and those new to librarianship, with or without degrees, but all are welcome to the conversation!

Let me be clear that this zine is just a starting point. As with any compzine (compilation zine), the writings are a little uneven, as people come to this topic from their own perspectives and experiences. I’m incredibly grateful to the contributors to being willing to share your knowledge and expertise! Readers, please get in touch with the creators if you enjoyed their contribution. And maybe let’s collaborate on an update in the future??

Violet Fox

@violetbfox

violetbfox.info

Dedication

This zine is dedicated to Kelly Swickard (1971–2021) & Jude Vachon (1964–2021).

I Was the Only Woman on the Tech Team

I was the only woman on the tech team, I also had to do storytime. When I asked why I was told everyone does everything. Except the rest of the tech team because delivering children’s services “wasn’t their thing.”

Danielle

World War II Reading Program in Sauk Center, Minnesota

For the 1943 summer reading program the librarian had a theme of “Bomb Tokyo”. On charts in the Reading and Reference Room the names of students enrolled were placed on “Battleships… and for each book they read they got closer to Tokyo”. Each child joined at the lowest rank as a soldier, sailor, flyer, or marine (if they were girls they could join as part of WAVES) and the librarian promoted them in rank as they read a certain number of books. Months later the librarian announced that the summer reading program had been highly successful, “with Tokyo having been repeatedly bombed by the older schoolchildren and the younger children backing the attack by building battleships.”

From “Main Street Public Library: Community Places and Reading Spaces in the Rural Heartland, 1876-1956” by Wayne A. Wiegand (2011), page 38.

If Libraries Aren’t Worried About the Tiny Things, How Can They Work on the Big Things?

Mary, a former school librarian, is raising her voice. “Muse in Lingerie? Fantasy in Lingerie?” I glance up. In front of Mary is a young woman who looks increasingly uncomfortable as the loud litany of titles continues. I know Mary is capable of speaking in a lower voice. I also know several nearby patrons are capable of overhearing this interaction.

Sara is making holds calls. It’s my first day at my first library job, as a page, and I’m shadowing her. She smiles at me as she dials the next number. There’s a long pause, then Sara leaves a voicemail. She says the title of the item being held in that voicemail. She seems confused, unaware of the privacy implications, when I ask if it is standard practice to do so.

Lee is joyfully greeting patrons as they walk by the circ desk. A teenager approaches and asks about graphic novels. Lee directs her to the youth department. I don’t bite my tongue; I chime in to let the patron know about the graphic novels section in the adult stacks. After they leave, Lee is aghast: “But those are adult books!”

Veronica is working in youth one night when 3 Black girls are in the teen room. She asks them to monitor their volume and walk while in the library. She doesn’t like their response. Rather than request support from the librarian on duty, Veronica calls the city police. Six white men respond. The cops check in with Veronica, but the girls have already left. The librarian on duty does not speak with the officers at all. Veronica does not face any consequences from library administration.

A Pride group is holding a drag queen story hour in the library’s meeting room. A large group of protestors shows up, some opting to join the event. One such protestor holds his Bible up over the room, chanting, praying, and modifying the lyrics of the songs being sung to harass the performers and audience. The library director watches, feigning powerlessness, claiming that the man’s actions are not in violation of the library’s conduct policy and he has “freedom of speech”.

Library school taught me that there is a document intended to establish values and ethics for libraries and their staff. Such values are supposed to guide us through smaller incidents like these – violations of privacy/confidentiality, censorship of materials, issues of access – in order to make libraries more equitable and accessible for everyone. Working in a library taught me that you can create all the documents, establish all the committees, and curate all the reading lists, but those are empty actions if they aren’t based on values that explicitly oppose the many forms of oppression causing untold harm in our communities.

KMF

@ckillgannon

Values and Agency in Library Organizations

Something you might not guess about libraries: though they espouse intellectual freedom, diversity, and democracy, they aren’t very good at honoring those things in their own organizations. Libraries typically have org charts that concentrate power at the top, and new ideas are too often drawn from the pages of the Harvard Business Review. In recent decades, libraries have been busy forming teams, being flattened, throwing fish, moving cheese, acting like a start-up, future-proofing, and being disrupted. We’re asked to prove our “value proposition” as we provide service to our “customers.” We must gather data to prove that we should be allowed to exist in a highly competitive and austere environment.

Capitalistic assumptions are potent drivers of library decisions. Think about these keywords as you explore job opportunities.

- “Change” is a word that has been haunting libraries for decades. Throughout the nineties librarians were told that change was scary but inevitable, that the future belonged to those who embraced it. More recently, the change narrative grew apocalyptic with theories of disruption and creative destruction. This notion of change is violent and dystopian, both frightening and inevitable. It’s an ahistorical and uncritical way to think about change which assumes library workers cling to stodgy, conservative ways, but must be forced by visionaries to do things differently, now, lest we be replaced by nimbler competition.

- “Irrelevance” is change’s evil twin. If we don’t embrace new things, right now, nobody will want us anymore. This is a curious fear. There are few municipal institutions that are as well-loved as public libraries, and it’s hard to imagine a university without a library, though there are those in positions of power who doubt they’re needed, what with Amazon and Google. But these days, the dominant narrative of How Things Work is through eliminating the competition and market dominance, so we fear losing market share to our competitors – which, in reality, they aren’t.

- “Value” is another keyword that is troubling when it’s singular. We’re asked to create dashboards that can communicate our worth to funders. In order to have lots of crunchy numbers to prove our worth, we’re encouraged to participate in the surveillance-industrial complex, collecting and analyzing behavioral data about our patrons for their own good. The corporatization of the library, the fear of irrelevance, and the drive to answer our questions with defensive data rather than with open-ended curiosity is part of a trend to concentrate power at the top.

It’s something to think about as you interview for jobs. Is this a place where my talents will be not only appreciated but allowed to thrive? Is decision-making shared? How about respect? Are creativity and experimentation encouraged and given time and resources to flourish? Pay attention to the signs. Look for slippages and disjunctures in the ways staff and administrators talk about the library. Think about whether the values (plural) you care about appear to be present in the ways the organization works – because too often they aren’t.

Barbara Fister

@bfister

barbarafister.net

The Emotional Labour of Libraries: an Australian-Aboriginal Perspective

Working in a library is already emotionally taxing. I’ve had conversations with academics who break down in tears over the phone, I’ve had men tell me I should smile more, and I’ve had conversations with aggressive patrons all the while having to keep an upbeat, welcoming disposition. Being Aboriginal in this industry comes with its own layer of emotional labour.

As information professionals, we’re experts at finding information and examining its validity, yet when it comes to questions about Indigenous culture or finding someone to assuage their white fragility, people forget how to Google and I am barraged with a thousand questions.

I was born into an Aboriginal family from New South Wales in so-called Australia, and three years ago moved to Queensland. There is not much distance between where I grew up and where I live now, yet the culturally differences between my family and Indigenous mob I’ve met here is startlingly different. I made a throw-away comment about this at work recently, as one does when recollecting the weekend over morning tea. This comment seemed innocent to me but sparked a heated conversation between myself and my white colleague, who continued to press for more information.

I was alone in this situation. I am the only Indigenous person in my team and the silence of my other colleagues empowered my contender to continue speaking. This is not the first time this has happened, and it will not be the last. The fact that I can say that sentence so confidently and the fact that I am supposed to just ‘get over it’ speaks volumes.

As a non-white person in this industry, I often feel unrepresented and I am unable to conform to colonial expectations. And I shouldn’t have to. A friend and contemporary, Nathan Sentance, wrote a blog post called ‘Diversity means Disruption’ where he questions why libraries do not do more to challenge whiteness. He says, ‘As [the] result of the invisibility of whiteness, diversity initiatives are often about including diverse bodies into the mainstream without critically examining what that mainstream is’ (Sentance, 2019).

There are programs to help promote information and cultural sensitivity such as workplace cultural awareness training and the National and State Libraries Australia (NSLA) Culturally Safe Libraries Program that outlines how to work with Indigenous collections. Yet, none of this training fully prepares someone to work alongside an Indigenous person and it still falls to Indigenous peoples to educate and validate their non-Indigenous colleagues.

If we wish to produce culturally safe spaces and encourage more non-white bodies into our libraries, we need to allow institutional disruption and change into our libraries, we need to value the expertise and experiences of Indigenous staff instead of prioritising the glaringly white status quo, and we need to learn to do our own due diligence instead of relying on our non-white colleagues to pick up the slack.

Reference

Sentance, N. (2019, September 27). Diversity means Disruption. Archival Decolonist. https://archivaldecolonist.com/2019/09/27/diversity-means-disruption-2/

Raelee Lancaster

@raeleelancaster

1971 Library of Congress Sit-In

On June 23, 1971, twenty-eight black employees of the Library of Congress were suspended for staging a sit-in along with about a hundred total black employees in the Main Reading Room. They had decided to protest the low pay and the discrimination in promotions they had faced for years. Most of the twenty-eight staff members who were suspended were deck attendants, who primarily pulled, delivered, and reshelved books for researchers. This job, which could be physically demanding, offered very low pay and few chances to move into another position at the library. Nearly everyone who had the job was black, as they are at the time of the writing of this article.

Two months before the protest, a group called the Black Employees of the Library of Congress (BELC) had led a tour of racial discrimination for the news media and the staffers of black members of Congress. According to an ALA report, 38 percent of the library’s employees were black, but they held 76 percent of the lowest-paying jobs.

BELC was led by a Library of Congress employee named Howard Cook. He explained many years later, “We saw what was happening here, where Blacks were qualified for promotions but were denied. Instead, we had to train these Whites, who later became our superiors.” Along with another black employee, David Andrews, the two founded BELC but soon came to realize that discussions and protests were not resulting in any significant progress.

In 1975 they filed a class-action lawsuit against the Library of Congress with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Cook retired in 1989, when the case was still unresolved but had moved through several layers of the court system. The Supreme Court refused to hear the case that year. A lawyer named Avis Buchanan took it on, probably because her mother was one of the plaintiffs.

Finally, in 1995, a US district-court judge ruled in favor of the plaintiffs for an $8.5 million settlement, the largest ever against a federal agency for discrimination. But the case did not end discrimination at the library. As of 2016 at least fifty others had sued the library for discrimination.

African Americans were not the only group that faced discrimination at LC. Women were in the majority, as they were at every library across the country. But while many women librarians had somewhat comfortable salaries, most of them were single, especially before the 1980s. These women were continually passed over for raises and management positions, with the reasoning that men librarians had families to support on one salary. In 1971, Barbara Ringer, who had long worked as assistant register of copyrights, sued for sex discrimination and won when she was passed over to lead the copyright division.

While we may revere the Library of Congress for its role as our national library, we cannot ignore its history of discriminating against both its black and women employees who have long been the engine that kept this enormous institution running.

This is a condensed and edited section from Chapter 32 of A Well-Read Woman: The Life, Loves, and Legacy of Ruth Rappaport.

Kate Stewart

kate-stewart.com

The Art Librarian

When I first became an Art Librarian, I was stunned by the diversity of books that our reading room boasted. The rest of the stacks were closed to the general public – think the Restricted Section in the Hogwarts Library. Only library staff, graduate students, and faculty could access the stacks. No one else really knew what was back there, unless they did a deep dive into the online catalog.

At first glance, the public spaces make it seem as if diversity is truly a core value of the institution and library. We’ve got a whole browsing shelf devoted to butch lesbian art! We’ve got a zine collection that reflects a wide range of topics, from Black Lives Matter, gender identity, birth, all the way to suicide. Almost all of our browsing shelves have at least a few black or Latin American artists featured, like Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker, or Frida Kahlo.

But here’s what people can’t see, or hear –

Most of the books on “primitive” art have been moved back to the stacks or to storage, put away but not gone.

90% of our reference collection is Euro-centric, and still reflects this even with moving half of the collection back into the stacks.

I’m often approached by faculty members to create browsing shelves for their classes. I’m also a person of color. Unfortunately it’s not uncommon to hear something like, “You look like you know what you’re doing, can you add some books on women and black artists to the shelf?” without providing suggestions for who those artists are.

I say all of this to argue that, as libraries, we need to do better.

Putting a bunch of books about diverse artists and topics in the reading room is not a long term solution to dismantling oppressive systems within libraries, or to make it seem like our collecting practices don’t still contribute to whiteness as an ideal. Simply putting the books that contribute to these oppressive systems back in the stacks or in storage doesn’t solve the problem either.

If you want to actively dismantle these systems, stop letting those old books sit on the dusty shelf and reflect your white silence. Here are a few suggestions for what to do instead:

- Use them to teach students about the lack of diversity in old books. For instance, compare a textbook published last year on Asian art vs a textbook on Asian art published in the 1970s.

- Use them for art projects. Get out the scissors!

- Donate them to a museum or archive.

- Throw them in the bin.

Similarly, don’t let the diverse topic books just sit there without explanation. Letting people know that the books are there is not enough. How are you helping ACTIVATE these books for library visitors? Get classes or groups involved with curating their own browsing shelves. Build programming around these shelves and invite people into a dialogue. And above all else, make sure you’re not the only voice in the room.

Anonymous

Did you know that libraries are not accessible? Did you?

Chances are, if you’re reading this, you’re in love with libraries. You want to help people. You are passionate about the hard work, the long hours at the reference desk, maybe even the sticky tack you use to hang up flyers with. (I have a friend that got into librarianship because she just LOVED creating flyers. Peak librarianship? Maybe not, but she’s got the spirit?)

No, libraries aren’t accessible. Strange. Your brows furrow. The place where “anyone” can get a book is still yet gate-kept. How?

An aspiring librarian who’s a rising senior at Emory University, I’ve learned it the hard way. Last year, I was selected to be an Association of Research Libraries Digital and Inclusive Excellence Fellow, and I worked at the Emory library system. I saw it all: the floppy disk collection, the rivalries, the stacks, the gum under the shared computer desks. Yep, I saw it all. But also, I learned very quickly that academic librarians and public librarians are two different kinds of people. Two different kinds of work.

I had a lovely time, don’t get me wrong. The most willing mentors, yummy lunches, amazing meetings. The conferences were some of the best experiences I’ve ever had in my life! In fact, the Georgia Libraries Conference (GLC) was the most pivotal experience for my young, budding librarian self.

As soon as we (me, the other fellow, and our two mentors) were revealed to be Emory folk, we were treated differently. No one looked us in the eye. The keynotes were quick to challenge us. We were also the only POC (me and the other ARL fellow) which was immediately telling, in two different ways:

1. Private libraries ARE snobby, and

2. BIPOC are minorities in librarianship regardless.

To be honest, maybe not knowing this was my naivete! But until I came to college I had no clue.

I was your typical public library kid. I learned how to walk at a library, talk at a library, took my SATs at a library, you name it. I LOVED libraries—they saved my life, and I love people. But at Emory, I was always pushed into the private library sphere. They were the more prestigious places and jobs. They had the most resources. But their user interface was mostly rich, privileged white people, half of whom didn’t use the library anyway.

Public librarianship was often derided. “Anyone can be a librarian!” I was often told. But they were the ones helping primarily low-income BIPOC. They were the more personable ones. They were the life-changers. But they were mostly white in staff.

I give you this brief take not to be rude. I love both library spheres. I love all librarians. But I had no clue how different they were. I’ve worked in curation, I’ve worked in archives. I’ve done it all. And with confidence, I can tell you this:

Libraries aren’t perfect. They have the potential to do SO MUCH good. But there are drawbacks to each type, and each field, and if you’re a BIPOC librarian, you need to be aware, and ready, to play their game. To protect your interests, and yourself.

Rest assured, though: it will be hard, but it will be worth it.

Lydia Abedeen

@lydia_abedeen

Library Systems are Not Perfect: Describing Transgender Children and Young People Using LCSH

Online library catalogues appear as a single interface to users, who are unaware that they are a mix of systems, standards and controlled vocabularies containing records created both from inside and outside the library. One of these controlled vocabularies is the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) – a list of headings used by many libraries to describe books and other items in their collections so that they are findable by users when searching catalogues.

Controlled vocabularies are works in progress and aren’t always up to date or free of bias. For example, two of the various LCSH used to describe transgender children and young people are:

‘Gender identity disorders in children’

‘Gender identity disorders in adolescence’

This is problematic because the category or broader term that these headings belong to is psychosexual disorders. This implies that being transgender is a mental disorder, or a problem or illness. The visibility of these subject headings online in a library catalogue could signal non-acceptance of transgender children and young people.

Other classification systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) and the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD) have moved away from using the term ‘gender identity disorder’. However, books published in 2020 are still being catalogued using these two LCSH.

In Australia, transgender young people are significantly more likely than other young people to experience depression, anxiety, eating disorders, suicidal thoughts, bullying, homelessness and discrimination (Strauss et al., 2017, pp. 15–35). Libraries should be a safe space where transgender young people can independently seek and access information relevant to them.

Libraries need to ensure that appropriate headings with a positive portrayal of transgender children and young people are consistently applied. Sometimes libraries use catalogue records provided by publishers and other sources, and may not have actively chosen the subject headings. They can check if they are using either of these two problematic LCSH, and use alternatives. Libraries can also consult the recommended reading lists of relevant support organisations, and check that any resources already in a library’s collection use LCSH such as ‘Transgender children’ and ‘Transgender youth’.

Even if the gender identity disorder headings remain part of LCSH, libraries can still ensure that relevant resources are visible to transgender children and young people, and their families. LIS students can look out for misrepresentations while they learn, initiate and contribute to online discussions, and bring their increased knowledge to new workplaces.

This zine article includes my personal views as an early career information professional, as I do not have lived experience of how the LCSH discussed would affect transgender children and young people. A Curtin University assignment (Perth, Australia) inspired this article, and a longer version can be found at:

https://neevq.wordpress.com/2020/07/21/how-lcsh-represents-transgender-children-and-young-people/

References

Strauss, P., Cook, A., Winter, S., Watson, V., Wright Toussaint, D., & Lin, A. (2017). Trans Pathways: The mental health experiences and care pathways of trans young people. https://www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/brain–behaviour/trans-pathways_easy-print.pdf

Niamh Quigley

@newneev

Segregation in Library Associations

When thinking about the problem of Whiteness in libraries it is good to remember that this isn’t just a random thing that happened, but a problem that was built on top of structural racism within the United States. People in librarianship then made choices to make these situations better, or worse, within living memory.

I’ve been doing a project to make sure state library associations have Wikipedia pages. Many didn’t. Putting these pages together meant delving into a lot of library association history. While Carnegie doled out money to build White and Black libraries (mostly White), he could have used his immense financial power as leverage to lobby for different outcomes, to lobby against segregation. He didn’t.

This theme—what can you do with your power and how much do you shrug and say “Well that’s just the way things are”—was seen repeatedly in the complicated history of library associations during the US’s period of legalized racism in the form of segregation laws.

The American Library Association—an organization currently headed by a Black President and a Black Executive Director—held a library conference Richmond, Virginia in 1936. Virginia was segregated. Black librarians couldn’t legally attend many conference sessions, and couldn’t eat meals at official conference events. Conference reports often were in passive voice “Black librarians were barred from many sessions… due to segregation” instead of a more active voice “ALA chose a conference location where Black librarians were unwelcome.” ALA later instituted a policy forbidding library conferences in segregated states. They did not meet again in the South until Miami Beach in 1956.

Many Southern states had de facto segregated library associations. When queried, you again would see the passive voice “library associations… reported no formal barriers to membership but reported that most African Americans chose not to join.” In 1954, ALA barred states from having 2 separate state chapters within the ALA. My favorite Wikipedia article to write was the short history of the North Carolina Negro Library Association which had a mostly-amicable merging with the NCLA during this time. In 1961 ALA passed a policy requiring state chapters to recertify and affirm that they did not practice discrimination within their chapters.

Some states dropped out of ALA rather than integrate their library associations. Louisiana and Mississippi chose to leave ALA rather than integrate. Alabama and Georgia left ALA rather than recertifying. You can bet that information is on their Wikipedia pages now. All state associations were forced to integrate after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed.

I think about looking for the helpers. The Virginia Library Association decided to have its meetings in schools and bring in their own food so that all their members could be together. The Faith Cabin Library project built nearly a hundred libraries for Black students in South Carolina and Georgia. E. J. Josey went on from lobbying ALA to change their racist policies to being president of ALA in 1984. We muddle forward together, but we should do better.

Jessamyn

librarian.net

I Worked for a Director at a Small Library

I worked for a director at a small library for six years who was a master of psychological abuse. He strategically and subtly seduced me, alternating between compliments and insults until I was thoroughly confused and dependent on his approval. He would get angry every time I tried to set limits or express my misgivings about our relationship. He would frequently suspect me of disloyalty and punish me by ignoring me or yelling at me or glaring at me. He made it clear that he expected me to be respectful and humble and submissive in every way while he criticized and degraded me. I left when I realized that he considered me to be a second wife to him and that he was demanding that same level of commitment and devotion.

All library employees, in every kind of library, should get informed about their rights and how to recognize harassment. You should know how to document everything someone does that makes you uncomfortable and who to report it to.

Anonymous

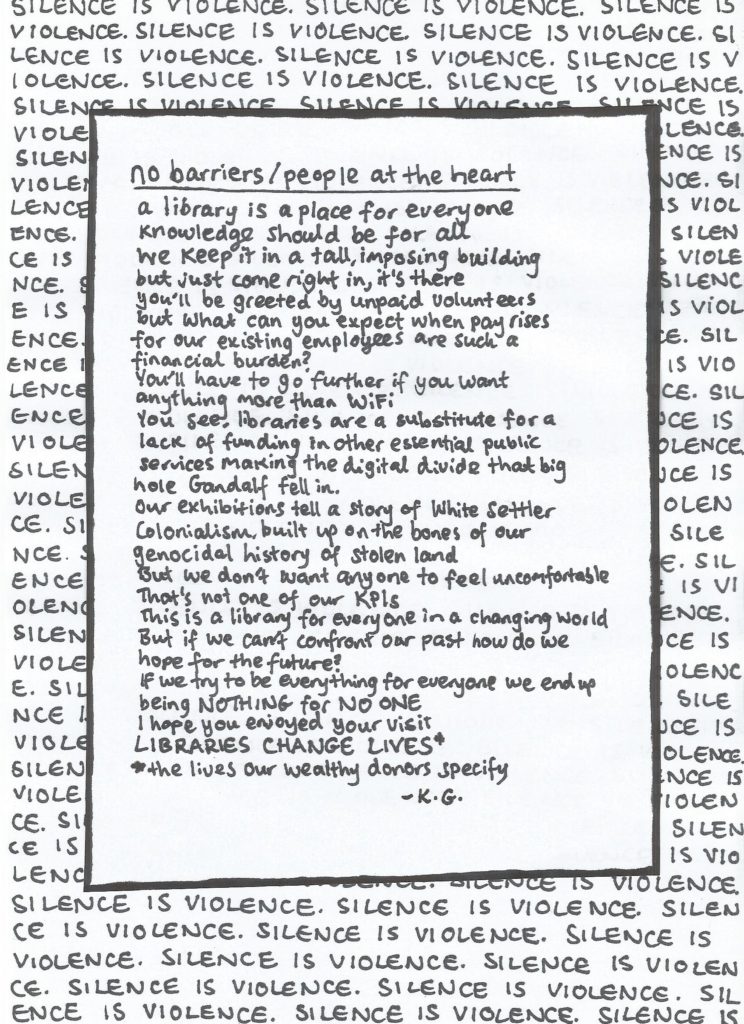

No Barriers / People at the Heart

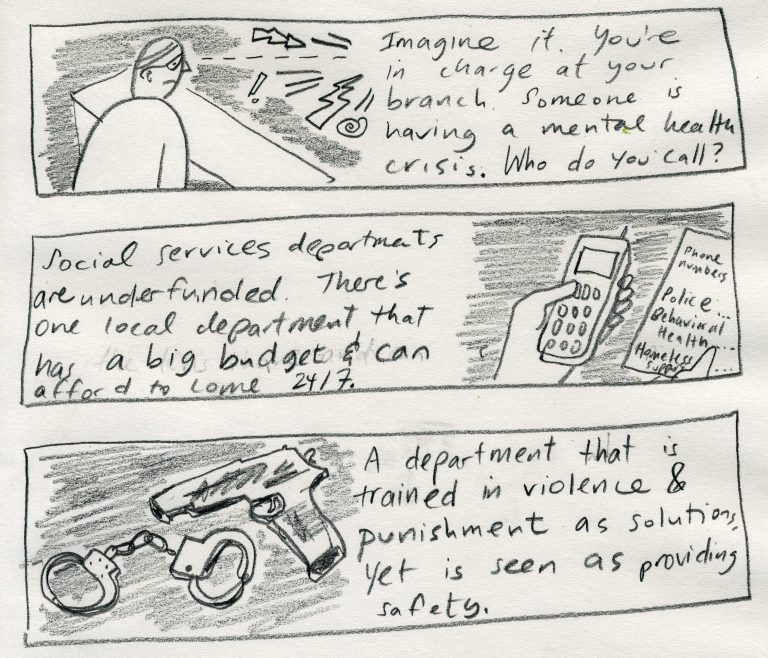

Calling the Police

Despite occasional inspiring protestations against government surveillance and a persistently stated commitment to intellectual freedom, the institution of the library is typically an enthusiastic partner with agents of state violence. Libraries bring in police and public safety officials to teach workers how to be properly worried about acts of mass violence. Cities require public libraries to turn over their buildings to police for staging counterprotest operations. And, inescapably, library workers are expected to call the cops on library users.

Sometimes calling the cops will feel like the right thing to do. It seemed reasonable to call the campus police when two students began physically fighting in the lobby, and library staff were unable to safely separate them. The fight fizzled out and calmer heads prevailed before the police arrived, but within minutes, a dozen cops, rifles at the ready, stormed into the library, sending students running scared. The library became complicit in one of several episodes at the university where the police force displayed characteristic animosity toward the majority Latinx and Black student body.

Other times, calling the cops will seem like the obviously wrong thing to do, but your colleagues will do it anyway. The cops certainly did not need to be called when a student let his non-student brother log into a public computer with his university credentials. But a white library worker imagined that this technical violation of the rules by two Black men was a physical threat. She called the cops. They escorted the two men out of the building in handcuffs.

And still other times, you will try to avoid calling the police, but the lack of adequate social support at your university or in your city will eventually lead to the cops intervening anyway. That is what happened when a library user approached a circulation desk worker and said they desperately needed someone to talk to about their stress and loneliness. After a lengthy conversation, the empathetic worker, with the user’s consent, called the office of student health. But the office of student health called the cops, who showed up and, claiming he was a danger to himself and others, led the student away in handcuffs.

Many library workers will enthusiastically partner with the police, and will call on them at the expense of Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ users’ safety and well-being without a second thought. But even for those who are hesitant to invite police into library spaces or refuse to do so at all, the partnership between the library and law enforcement is inescapable. The library is an institutional partner with the police and the state, and that means the library is complicit in the violence the police perpetrate on its users and its community. Until that partnership is severed, libraries cannot claim to be welcoming, safe, inclusive, or committed to justice.

Caleb

Tips for New White Librarians from a First Nations Librarian from So Called “Australia”

Understand whiteness — and name it and challenge it

Whiteness has shaped librarianship and libraries. It influences library spaces, services, collections and recruitment thus staffing demographics. It’s why we consider librarians of Colour as diverse librarians instead of just librarians, something that is reserved only for white librarians.

We need to abolish whiteness like other interconnecting oppressive structures. But we cannot abolish whiteness in libraries if we pretend it does not exist, if we can’t talk about it. That is how whiteness sustains itself and will remain the invisible default. And how libraries aid and have aided whiteness & white supremacy.

White librarians have often had the privilege to not learn about whiteness and racism. So start learning about whiteness. Libraries will remain whitopias if this is not addressed.

Stop the myth of library neutrality

I talk about this topic so much because I hate the complicity and enforcement of white supremacy done by libraries under the guise “neutrality” or “objectivity”. Libraries have reinforced and reproduced the dominant social order and the values behind it. This is not neutral, and consequences of the dominant social order have not been neutral.

Libraries have never been for everyone and have never been neutral. Reinforcing this has detrimental effects on those most marginalised in our societies. So, question colleagues, question library and archive literature or anything else that claims libraries are or should be neutral.

Be political, it is not an option for some

Like the above point, librarians, we are not neutral. We need to collectively challenge institutional demands for us to not be political. Avoiding “politics” is a privilege your colleagues of Colour may not share as our lived experience is political.

Challenge the myth that libraries are inherently good

Libraries need to do to be good. Libraries simply existing isn’t enough if they are not self-reflecting on their own complicity in oppressive structures. You’ll hear statements like libraries and archives as pillars of democracy but what does that mean given the lack of marginalised people’s perspectives and voices within those organisations? What does this say about democracy?

Constantly question who’s being centred

This is aimed more towards those engaging in anti-racism work, often excited white people who want change can centre themselves in discussions about race and decolonisation. This can erase the work of colleagues of Colour and something you should be mindful of. As a white passing/fair skin First Nations person I often have to question how much space I taking up in discussions of whiteness and libraries and who is missing from the discussion and is palatability to colonizers at play when I get invited into certain conversations.

Diversity is not a synonym for decolonisation. Diversity is not a synonym for anti-racism.

Read Decolonization is not a metaphor by Tuck and Yang.

Nathan mudyi Sentance

@SaywhatNathan

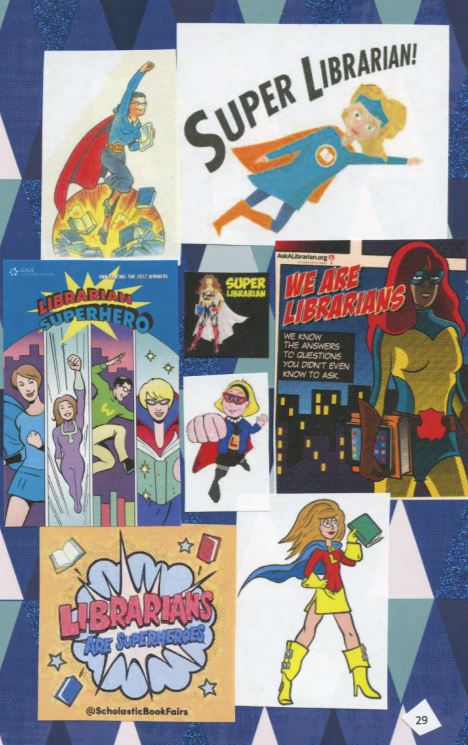

“Librarians are superheroes!”

“Librarians are superheroes!” Library workers hear this rhetoric frequently; some even say it themselves. As someone affiliated with libraries, how does that message make you feel? Many in LIS look at those messages with pride, thinking about the lives that library workers impact positively. It may represent feeling appreciated in a profession where, like other pink collar professions, status and payment in line with our education are sorely lacking. Some may roll their eyes, finding it cringe worthy or obnoxiously earnest.

I’m the killjoy who thinks this framing is actively harmful. By billing librarians as superheroes, we’re portrayed as superhuman, not subject to such needs as “respect” or “fair working conditions” or “a living wage.” More importantly, this portrayal places us above criticism, encouraging us to overlook the problems within the profession: the racism, the transmisia, the ableism, the classism. (See Fobazi Ettarh’s writing on “vocational awe” for more reflections on how we deflect critical self-reflections on our own work.)

In messaging targeted to children? Maybe it’s fine. But “superhero” phrasing is often used to market libraries to our patrons/taxpayers, or, even worse, used by vendors to market to librarians. Next time you see this wording or something similarly uncritical and complimentary, take a moment to reflect on what’s being communicated and what that messaging is teaching us to ignore.

Violet Fox

Librarians are revolutionaries?

Librarians are revolutionaries? Ha! Maybe some are, but we can’t make a blanket statement that pictures us as an ultimate force for change if we can’t even decide that Nazis are universally bad and have no place promoting their agenda in our buildings. We can’t say we are progressive if we can’t admit that libraries aren’t neutral. We can’t say we are forward-thinking unless we prove we are fighting for marginalized patrons. We can’t say we are thought leaders unless we realize and admit we perpetuate ingrained injustice.

There are many in the field doing amazing work, but as a whole we leave a lot to be desired. We constantly offer lip service to progressive ideals but lack the conviction to make a stand. We are extremely risk averse and it can be understood at times. We need the public on our side, especially in these times of austerity. But we support our communities by supporting our patrons. This means making an inclusive space people can use without fear of monitoring or judgement.

We need to prove our libraries are for everyone. We have enemies and while we want to say we support everyone who walks through that door we constantly prove otherwise. We constantly judge, marginalize, stigmatize. We constantly put down the homeless, the mentally ill, undocumented immigrants and many more marginalized people in our communities.

We do this while constantly purchasing and promoting hate-filled propaganda and exclude the voices of those who need to be heard.

We ignore the privacy of our patrons because we don’t read the terms of service of the products we purchase. Either that or we don’t understand the implications of what this may mean. Patrons trust us, and we need to prove we are worthy of that trust. This means going the extra mile and taking care of them even when they don’t realize they are at risk.

We offer vital services to our communities and this cannot be understated. But we can be so much more. We can be a true voice for good, we just need the courage to stand up for ourselves and our patrons.

We can’t call ourselves revolutionaries as a field when we can’t even say Black Lives Matter. We can’t call ourselves a force for good until we realize how the police presence in our libraries limits people’s comfortability and access.

We talk a big game, but we’re too afraid. We need to make noise and join the fight. That’s the only way we’re going to prove we have earned our place.

My Last Day at the Public Library

I had regular creeps:

Mark from the Flea Market, Miami Guy with Elephant Teeth

here is the last thing Bird-Watching Misogynist said to me:

“I once saw

Last week

or the week before

a little boy on banding day

held a cardinal

till it pecked him bloody

the conical beak

was wicked,

its feathers

reddened.

When I was a boy the herps–”

And here he stopped himself

assessing my sex, my race

my intelligence

“The snakes, lizards and frogs

were what I was interested in birds

are so different”

And I said

“But they came from

the same place.

Not so different”

And he said

“We all came from

the same place

If you go far back enough.”

Then my coworkers faked a call

and stole me away and laughed

at the desperate ones

the lonely ones who

can’t help themselves

but I knew

and had known

that he never reads the books

he sits with he

just watches

the people

like clutching a bird or

a ball of snakes

fascinated by your own

humiliation and apathy

I was watching back, I knew

if you go back

to the same place

there’s a moment where

little boys

(and yes,

the rest of us)

climb out from the swamp and

sprout leathery tails but

then some of us

covered in blood

sick and captive

writhe from the fist

and fly

JAK

Melvil Dewey: Father of Modern Librarianship & Racist Creep

Melvil Dewey’s name is most often associated with Librarianship due to the Decimal Classification System that carries his name. But did you know that he also championed spelling reform, and was an early promoter of winter sports?

As Melvil Dui (spelling reform) he was one of the founders of the American Library Association. Less well-known was his persistent sexual harassment of women – his unwelcome hugging, unwelcome touching, certainly unwelcome kissing were noted by biographer Wayne A. Wiegand. When he opened the School of Library Economy at Columbia College he requested a photograph of each female applicant due to his belief that “you cannot polish a pumpkin”.

Then there were his racist and anti-Semitic views, at the Lake Placid Club, a place where Dewey envisioned educators finding health, strength and inspiration at modest cost; he banned African-Americans, Jews and others from membership.

Many people at this point may think that his views were common and accepted at this time but they contributed to a petition demanding Dewey’s removal as State Librarian because of his personal involvement in the Lake Placid Club’s policies, this led to a rebuke by the New York State Board of Regents causing him to resign.

He was later forced out of active membership of the American Library Association after he made physical advances on several members of the ALA during a cruise to Alaska. In 1930 he was sued for sexual harassment by a former secretary that cost him over $2000 to settle out of court.

At the 2019 ALA Annual Conference his name was stripped from the Melvil Dewey Medal – awarded for creative leadership of high order, particularly in those fields in which Melvil Dewey was actively interested: library management, library training, cataloging and classification, and the tools and techniques of librarianship.

Find out more about Melvil Dewey:

Stuff Mom Never Told You podcast, episode “Librarians part 1”

Melvil Dewey, Compulsive Innovator

Bringing Harassment Out of the History Books: Addressing the Troubling Aspects of Melvil Dewey’s Legacy

State Librarian Dewey: the Real Issue Involved in the Demand for His Removal (1905)

American Library Assn. Strips Name of Dewey Decimal System Creator from Annual Award

Matt Imrie

@mattlibrarian

Rock the Boat with Your Privilege

Divorce your view of individuals and mentors from your view of the field. The vast majority of my colleagues have been smart, collegial, and enterprising information professionals. Unfortunately, though, libraries are still very white and often have cis white men filling administration roles.

You should know that many hiring committees are making it up as they go along, even if they have guidance from HR. Biases and prejudices are almost certainly at play. Volunteer for hiring committees if possible and push back when someone tries to strip identity from their interview assessment. Many people think they can take an identity-blind approach to interviewing but then ultimately form assumptions based on race, gender, age, etc. Question someone when they say a non-cis male and/or non-white candidate “doesn’t seem like a visionary leader.” Be wary of cis white guys who use hand-wavy tech jargon to fail upward. Be extremely self-aware and critical of your own biases and prejudices. If you’re not Black, make a point of following Black information professionals who publicly critique the field and take what they say seriously. Do not fall for the “libraries are neutral” trap.

Be aware of when your own privilege benefits you and get used to the discomfort of calling that out. Spoiler: if you’re a cis white guy like me, privilege often means higher-ups assume you can learn what you need to know on the job. A lot of people don’t get that benefit of a doubt. Similarly, share your salary amount freely with colleagues once you’ve ingratiated yourself with them, especially if they are doing similar work as you. Some places will do equity raises, but only if someone points out the disparity.

Anonymous

My Journey as an Assistant Professor

When I began my journey as an assistant professor in 2014, I was excited. This new position offered me the opportunity to do things I never tried, including teaching Information Literacy and being a cataloging department head; I loved these opportunities. Librarianship is not my first career, yet I wanted it to be my last, as a tenured faculty member. However, our faculty chair left four months after I started, and ten months into this new position, I was diagnosed with a brain tumor. I was out for six weeks for surgery to remove that tumor and I returned to a new faculty chair. Once I returned to work, I discovered, contrary to my understanding and our collective bargaining agreement (CBA), faculty chairs were not “supervisors”, but this chair tried to supervise me. We did not get along from the word go.

The chair’s role is to manage faculty concerns, include mentoring new faculty so they are successful in tenure. This one has failed, as so many new faculty have not received tenure. Most leave, but that is their story. Early in my second year, my work performance was found lacking. It could have been the brain tumor, but rather than help, I was put on a professional development plan (PDP). This was a disciplinary process as I learned later, but it was not presented that way. The Dean who hired me retired; the library had two interim deans who leaned heavily on the opinion of this chair. By this time, I was removed as a department head and relegated to be a research librarian. The chair gave me busy work such as finding grants as my main duty. I was not doing the work of a faculty member. I eventually felt less like a faculty and more like a paraprofessional. She directed me to stay within each plan she helped create, giving me minimal direction in my reappointment process and writing very detailed letters for each reappointment deadline, outlining negative failings in my tenure, and making little of any successes.

I underwent several surgeries as a result of the brain surgery which resulted in the Provost granting a tenure extension in my fourth year. Throughout my tenure I continually provided instruction, reference, outreach, professional development, service, and scholarship. Working with the faculty union, we discovered that I should have not ever been placed on a PDP, as that procedure was designed for post-tenure review for tenured faculty! Yet the chair continued to write extremely lengthy and negative letters for me every time I went for reappointment.

My reappointment failed and when I turned to the union to defend my non-appointment, the union said they could not make the case that I had continually developed my faculty skills given the many years of negative letters from the faculty chair. From my experience I believe library faculty will benefit from mentors outside of the library knowledgeable to the various duties of librarians. Then, perhaps, others may avoid what I went through.

Julie Carmen

newmedievalart.org

Assumptions Are What We Do Not Realize We Are Making

Assumptions, by definition, are what we do not realize we are making. This best describes my observation of a very subtle and unintentional form of bias I now write about. I write this anonymously in order to avoid embarrassing former colleagues. Partial disclosure: I am an old, straight white guy.

At a small academic library the 3 reference librarians range in ages from mid-20s to early 30s. My director asked me to run a meeting with these librarians in order to select a 4th one for an open position. These librarians consist of M, a young straight white woman, R, a young straight white man and G a young gay white man. They have all gone through this interview process when we hired them within the last 1-3 years. All our interview questions include one about “multiculturalism.” The Institution serves a large number of foreign students and faculty so the librarians thought it best to ask applicants to tell us about their experience working with people from diverse backgrounds.

During this final meeting the choice comes down to two white men (we’ll call them Applicant 1 and Applicant 2). Applicant 1, a straight white man and a close friend of R’s, chose to move across the country to take a job in Florida but now hates both the job and the location. Throughout the searching and hiring process R has repeatedly urged us to help rescue his friend from the consequences of his own decisions by hiring him. Not only that, the Library Director put R in charge of the initial process, including the initial screening of the applicants. R has no managerial nor hiring committee experience before now. M speaks glowingly about Applicant 1. Most of the conversation centers on how much they would enjoy working with Applicant 1. M says that during Applicant 1’s interview she made some pop culture reference and then he came back with a snappy answer then it was “instant repartee.” R and G both agreed that No. 1 would be a lot of fun to talk to and great to have as a colleague.

They were about to agree to hire No. 1 when I interceded. I pointed out of few facts. First, Applicant 2 had job experience relevant to the specific duties of the position and 1 did not. The 3 librarians had initially glossed over this by saying that “Applicant 1 can learn, he’s a smart guy.” I pointed out that if relevant experience is not a factor then why did we ask for it in the posting and ask questions about it during the interviews? Then I pointed out that the discussion I heard focused entirely on how much the three personally like No. 1. I agree, I explained, that hiring someone who fits into our existing corporate culture is a very important factor, but it should not be the only one. Then reminded them about the “multiculturalism” question we ask at every interview: “On the one hand, we say we value multiculturalism and that we must hire people who can work well with people of various nationalities and cultures, but you are only willing to hire someone who gets M’s pop culture references? How multicultural is that?” That last comes as close to verbatim as I can remember of what I said. I let the stunned silence hang for a moment. I think M had an epiphany. I then pressed on.

Regarding how well someone fits in with the three of you, did any of you find any reason why Applicant 2 would not? I then consulted my notes from the interviews, pointing out specific instances of Applicant 1 giving vague answers to our questions and/or pivoting to tangential topics. I contrasted that with Applicant 2’s more direct responses and one specific instance of him admitting he did not know something rather than deflecting as No. 1 did. More discussion followed. M and G changed their minds and we hired Applicant 2. A white male librarian makes a poor life choice then we’re supposed to give him a job to fix it?! But we’ll ask him about multiculturalism in the interview.

Gregor Samsa

Why I Quit My Job

When I quit my job after eight years, my boss asked me if there was anything in particular that had happened to get me to that point. I had sobbed in a meeting with her and HR two days before when I was put on probation for two months, so there was that. She had written me up three times and called me into her office to scold me many other times over the two-ish years before that. But I had other reasons.

Background: I worked at a public library. On purpose. I went back to grad school to get my MLIS so I could continue doing community education work in a new way and at a higher pay rate. I am in love with what public libraries can be–empowering, community-fostering, non-commercial spaces that offer programs and services for free. Amazing!

When I first got there, the director had raised 57 million dollars for the capital campaign to renovate library buildings, but had ignored other financial issues. I advocated for the library—in my free time because I was told it couldn’t happen during my work hours—including throwing an awareness raiser that 200 people came to, getting artists to make posters asking for support for the library and distributing them. A library tax that the city voted yes to and other new revenue streams led to more financial stability. The administration then cut part-timers’ hours (including mine) with no explanation.

Many years we would wait for news on the part-time budget at the beginning of the year and often have our hours cut, again with no explanation. Often we were told we had to work lots of hours at the end of the year, because more money became available and we had to show that it was necessary so that we would possibly get that amount for part-timers the next year. I was on partial unemployment at one point.

The library had become more and more retail-ish. Before I got there, there was a shift from using the word “patron” to using the word “customer”. I refused to say customer and did get away with that. Among other games, our manager made us play “Upsell Bingo”. We got Bingo cards that had resources or services listed in the squares and there were prizes for getting patrons to take us up on our offers. Competing against coworkers and “upselling” in a noncommercial space = 🙁 .

Interactions then had an element of performance for management instead of participation in relationships with patrons At one point the word was that upper management was watching us on the security cameras. It’s an awful pressure that ruins the beautiful interactions that take place all the time between good public librarians and patrons. The interactions really are amazing as long as you’re available, knowledgeable about what might help someone, and trustworthy in patrons’ eyes. The fact that this is a community space should have meant that I wasn’t selling anything and that patrons and staff should interact in a mutually beneficial way. These are crucial differences between our space and other spaces, differences that patrons for the most part value, and that I find essential. Essential as in it’s the essence of a public library and essential as in it’s sorely needed. People want to belong, share some of the ownership, and be supported, not be manipulated.

We were told that we’re not allowed to read at work, not even in the staff office when we’re off the reference desk. We were allowed to read online articles for professional development, which were defined more as writing about the profession as opposed to our subject areas. We were required to post book reviews and lead book discussions as part of our jobs, so we had to read other materials to do our job. Also, good librarians know their collections, so they need to be reading those materials and reviews of them. Our manager said it wouldn’t look good if upper admin saw us reading, even in the staff office. So most reading for work was done in people’s free time and was unpaid, including hourly part-timers. It’s absurd and sad to me that there isn’t support for a culture of reading IN A PUBLIC LIBRARY.

When I was unable to support a request to host an event from Microcosm Publishing because of their alleged history of abuse and bad business practices, they contacted the library’s HR department, dropping the words lawsuit and slander. It resulted in a brutal shitstorm that included me being suspended without pay for a week, instead of a thoughtful conversation toward understanding and support for the fact that I was protecting the library’s reputation (and mine) in a community I had been working in for seven years. Community work is about relationships and trying to do and support good work. It sometimes involves calling people out. Customer service means the customer is always right, even if they’re an abusive asshole. In the meeting about this, I was told that “we don’t take a stance”. Library neutrality myth at its finest. I was also reprimanded for “censoring” the publisher. Then I was told that I couldn’t discuss the situation with anyone, especially not at the zine librarians unconference I was heading to in a few days, among my most valued colleagues.

We couldn’t talk truthfully about our needs or even departmental issues, so problems didn’t get solved. I discussed ongoing IT issues that severely interfered with our work at a staff meeting and was belittled by my manager, cut off, told angrily that it was a great place to work, then written up because I responded to all that. Our manager set the agenda for meetings, told us her/upper management’s plans, asked for feedback, and 99% of the time there was no feedback or only positive feedback because we all knew that she hated disagreement. There are countless problems that were not addressed because 1. no one wants to bring it up, 2. it was brought up by a staff member but with zero response, 3. it was conveyed to those who could do something about it but they did nothing. Management didn’t request accountability unless it affected their own bottom line.

I see all of this as the worst of what retail is, what capitalism is—a pretty impossible situation, really. The place didn’t work nearly as well as it could for staff and patrons—good staff are dying, the other people gave up sometimes years ago, and the real, important service work is almost impossible to get done. Management is comfortable and service isn’t quite bad enough to provoke change/outrage, thanks to those staff members who care enough to handle the disregard for their own needs. I have seen this many times before in my (gendered) community and service jobs. Depressingly enough, this is not unique or new.

I was disgusted and my manager knew it and without self-awareness about it was trying to break me or get me out of there. I sucked it up so much more than I ever had in jobs before because I had a great love for the work, but then had to get out. I got myself out. I am not broken, just very deeply sad. I was angry for years but that wore me out.

Jude Vachon

“Accommodations Provided on Request”

The “Libraries are For Everyone” sign on my building has a picture of a person in a wheelchair on it.

Our programming posters say “accommodations for persons with disabilities provided upon request. Please contact your library with two weeks’ notice.” (Programs don’t appear on our front page until a few days before, at best.)

The building codes dictate shelves must sit at least 36 inches apart to give room for chairs to turn.

My tape measure says they’ve crept to 34, 32, 33, 30.5.

The patron bathroom door has the universal blue symbol on it.

The door opener has been broken for months.

We have four accessible spaces!

They block off three for the delivery truck in the mornings.

The ADA says we can’t be overlooked for needing accommodation.

Our job listings say “must be able to hear, speak, feel, see, sit, stand for lengths of time, crouch, bend, lift up to 50 lbs.”

Our administration says “equity, diversity, and inclusion are important to us!”

Our supervisors say “you need a doctor’s note to wear that wrist brace.”

Our communications department says “we’re a valuable public service and we listen to our stakeholders.”

Our HR department says “we can’t accommodate you. We’re trying to run a business here.”

The pandemic sweeps through. Everything changes overnight. Our doors close, our services shift, our patrons demand. Our supervisors and admins stay home, but we get shoved back into the building and told to figure it out. The taxpayers want books and the all-important DVDs. They pay for this service, these stakeholders. Services to the home-bound cease.

Who are libraries for?

Helen Wheels

Should Children’s Librarians Care About Defunding the Police?

Originally published at https://www.alsc.ala.org/blog/2020/08/should-childrens-librarians-care-about-defunding-the-police/

Lisa Nowlain

lisanowlain.com

Mildred Rutherford, Historian General of the United Daughters of the Confederacy

Rutherford led a crusade to expand the surveillance by historical committees to shape up private institutions and prevent backsliding by public ones. In 1919 Rutherford published A Measuring Rod to Test Text Books and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges, and Libraries. The UCV [United Confederate Veterans] adopted this measuring rod as a set of criteria for “all authorities charged with the selection of text-books for colleges, schools, and all scholastic institutions” and requested “all library authorities in the southern States” to “mark all books in their collections which do not come up to the same measure, on the title page thereof, ‘Unjust to the South.'” Here are some of Rutherford’s instructions to teachers and librarians:

• Reject a book that speaks of the Constitution other than [as] a compact between Sovereign States.

• Reject a text-book that […] does not clearly outline the interferences with the rights guaranteed to the South by the Constitution, and which caused secession.

• Reject a book that says the South fought to hold her slaves. Reject a book that speaks of the slaveholder of the South as cruel and unjust to his slaves.

• Reject a text-book that glorifies Abraham Lincoln and vilifies Jefferson Davis.

• Reject a text-book that omits to tell of the South’s heroes and their deeds.

From “This Mighty Scourge: Perspectives on the Civil War” by James M. McPherson (2009)

Collages by Becca Maree

Becca Maree

@biblioghoul